Hardware Vulnerabilities: Meltdown and Spectre and how to protect yourself

Introduction

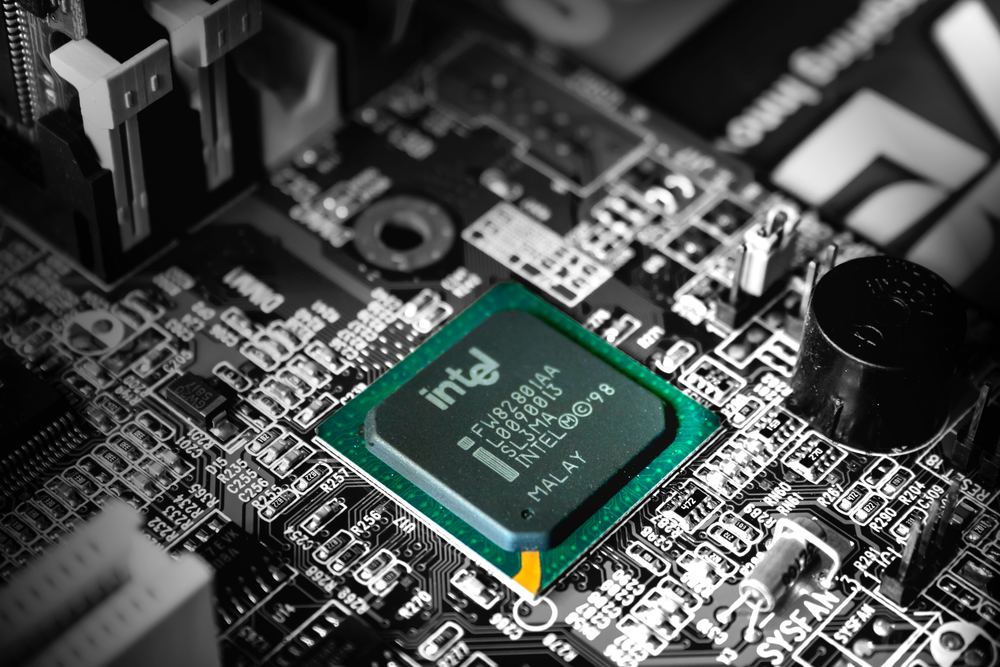

Meltdown and Spectre refer to 3 variants of hardware vulnerability found by the Google Project Zero Team and various other academic institutions and field experts. Unfortunately, these vulnerabilities exist on practically every piece of commercial hardware made since 1995. Companies such as Intel have already begun to produce newer chips that aim to address these vulnerabilities. All hardware manufacturers are actively working on rolling out software updates to secure older chips.

Now classed as a larger part of Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs), we think it’s important for developers to understand what these risks actually are, how they work and what that means for a developer. This article aims to contextualise these hardware risks and what you as a developer can do to protect yourself against these risks.

We will cover:

- The nature of the threat (as seen below)

- Speculative Execution in CPU architecture

- Mechanism for Meltdown

- Mechanism for Spectre

- Steps to mitigate hardware vulnerabilities

Reading time: 7-10min

The original 3 variants have the following associated CVE IDs:

To scan your virtual machines or any other Linux nodes for other common vulnerabilities, see this tutorial on how to do a CVE scan.

In short, if you have a chip/processor in your device (which you will), then you are at risk. However, there are ways to protect yourself in the interim. The good news is that the original vulnerabilities were addressed in early January of 2018. If you have updated your machine since then, you are protected at least from that. However, even as recently as August , further Meltdown and Spectre exploits have been found, and more are likely to come.

Speculative Execution

The Meltdown and Spectre vulnerabilities exist due to a functionality in modern processors known as Speculative Execution. Indeed, Spectre derives its name from this process. Speculative execution is an optimisation method employed by hardware that carries out some ‘speculative’ function in order to predict future tasks.

The key point to note about this is that the pre-calculated task may not actually be needed, but is done to save time, thus greatly increasing computational speed. If the speculated branch is not needed, its computation and the changes that would have been made are discarded by processor.

In modern processors, speculative execution is used in branch prediction in pipeline processes to reduce the cost of conditional branching. Essentially, each pipeline can have several architectural branches which carry out this speculative execution. These branches occur when a conditional option exists within a program. If a program depends on these conditions and a pipeline waits for this condition, computation time is essentially lost in wasted clock cycles. Speculative execution instead branches off into these different predictive branches and pre-calculates a conditional option before it happens.

Typically, speculative execution is 95% accurate and greatly increases clock speed. If a branch is incorrect, it is discarded before changing any memory addresses permanently, although not without leaving a time footprint. It is these ‘misspeculations’ that can be exploited, ultimately exposing vulnerabilities in a system.

Meltdown

Meltdown allows processes to read all protected memory and is currently seen as an Intel specific vulnerability. Meltdown occurs due to a technique known as ‘out-of-order’ execution. While out-of-order execution and speculative execution are two different techniques, they are often used in conjunction with each other. This is what Meltdown exploits use.

Out-of-order execution is employed by using all available execution units in a CPU to carry out instructions in a single program without maintaining their order. This means that if a program is executing, that unit does not need to wait to complete its task before another unit can move to the next in the sequence. This results in what we commonly refer to as parallel computation. However, an issue arises when an instruction in the sequence requires some permissions before execution, such as writing data to a specific memory address dedicated to the OS, or writing encryption keys to some address. Speculative execution allows for these out-of-order instructions to be computed speculatively without needing permission (on the basis that if incorrect these results could be discarded). This data is then stored temporarily in the CPU cache, and this could then be exploited and seen in a virtual machine container by an attacker through some side-channel. In Intel specific hardware, all out-of-order execution is done speculatively hence the vulnerability.

Spectre

Spectre is the name given to two variants of hardware vulnerability, both of which exploit speculative execution (hence the name Spectre). Spectre attacks, unlike Meltdown, do not focus on out-of-order instructions which bypass permissions, but rather on the conditional branching system discussed earlier. There are three different buffers that can be exploited. These are cache structures within the CPU. The first is the ‘branch-predictor buffer’ which ‘guesses’ which conditional should be taken based off some previous logic or probability. In order to carry out speculative execution of indirect branches, the addresses of where these instructions will be carried out needs to be computed first, and their results are temporarily stored in the ‘branch-target buffer.’ Once all these are computed, when an instruction is actually called a third buffer needs to predict where to ‘return’ the executed instruction to. These return address is stored in the ‘return address buffer.’ The two main variants of Spectre, V1 and V2 exploit this using 2 different methods.

V1 is named Bounds Check Bypass. What this essentially does is bypass bounds checks for an array and can lead to access of memory addresses outside the bounds of that array through speculative execution before the bounds check is complete. It can also similarly affect branch prediction; an attacker can deliberately mistrain this a predictor and access the mispredicted branch.

V2 is done by direct injection, known (unimaginatively) as Target Branch Injection. The branch-target buffer can be ‘injected’ with ‘bad’ data thus poisoning the branches. This can then be used to jump to an attacker’s gadget, a piece of malicious code, that will then be run giving an attacker access to a particular memory address. This can be similarly done to the return address buffer. Inbuilt mitigations for poisoned branches already exists known as retpolines which can be used to trap speculative branches so that they do not execute gadgets. Hardware companies are already using this to protect against V2 variant vulnerabilities.

Protecting your Hardware

Required Skill Level: N/A Time to complete: Dependent on your internet connection, but no more than 15 minutes typically.

The problem with Meltdown and Spectre is that these issues are found at a hardware level. But short of purchasing new hardware free of these vulnerabilities (note that Spectre V-1 has not been addressed yet by Intel, and Spectre V-2 has not yet been addressed by AMD), you are reliant on software updates to protect your systems. Additionally, as time goes on more of these vulnerabilities are being continuously exposed, so buying new hardware is not the solution.

Older systems have reported being slower, especially in read/write speeds since Meltdown and Spectre patches, so expect a drop in performance. However, for chips in manufacturing in the last 10 years, only up to a 7% performance drop has been seen.

There are 5 steps you can do to effectively reduce these risks:

1) Update your operating system(s)

Although Meltdown and Spectre operate at a hardware level, the most common operating systems roll out software updates that can also address and mitigate these risks. Keep up to date with operating systems and consider enabling automatic updates. Make sure you update your distribution’s kernel through sudo apt-get dist-upgrade.

2) Update your firmware

Companies like Intel frequently release updates for the microcode in their firmware in response to new variants in Meltdown or Spectre vulnerabilities being found. However, Intel typically prioritise updates to chips developed in the last 5 years so consider older chips to still be at risk. Before updating, ensure your data is backed up as bugs in the updates have been prevalent in the past.

3) Update your browser

Spectre attacks can happen through your browser with an attacker being able to read sensitive information from a browser instance, say online banking. Proof of concepts show that JavaScript code can be used to exploit CPU weaknesses. For Chromium based browser users, you need to manually enable strict Site Isolation.

4) Update any of your other software

Any software that interacts with your CPU architecture or operates inside your operating system’s kernel is open particularly to Spectre attacks. Systems with gaming software or additional graphics cards may be susceptible. Nvidia have released driver updates for their cards. Note that IoT devices are also at high risk. Things that operate on your network and access your system like printers should also be updated routinely. There is no blanket way to update these systems other than running normal upgrade commands such as sudo apt-get update && sudo apt-get upgrade.

5) Update your firewall settings

The easiest way to exploit any system is over the internet. Secure your ingress traffic in particular to only IPs that you trust and avoid interacting with unknown advertisements, hyperlinks, etc.

Implications

The good news is that no actual attacks have been recorded ‘in the wild.’ However, this may be due to the fact that recording such an attack would be unlikely as the effects would not be recorded in any measurable way. Fortunately, the risk and likelihood of such attacks is relatively low given the difficulty of execution. Right now, it would be seen as a very user-targeted attack. However, that isn’t to say it isn’t possible, and as hardware and computing speeds continue to become more sophisticated, the likelihood of such attacks increase. Already, Meltdown is a fairly significant risk as a Meltdown breach gives an attacker access to a system’s entire memory, and an attack can come via some online interaction using JavaScript. Fortunately, most browsers automatically patch and browser vendors are actively working to protect against timing attacks.

More broadly, it is possible these vulnerabilities can be used to escape virtualised containers in systems like Docker or Virtual Machines. These containers are supposed to be isolated processes, exploits of these could be used to impact your main system.

Conclusion

It is absolutely vital to keep your system updated. Since the original Meltdown and Spectre vulnerabilities were highlighted, several spin-offs have since been found:

- Foreshadow, 2018

- SPOILER, 2019 , paper here

- SWAPGS .

A fourth variant of Spectre was also discovered in May 2018 using Speculative Store Bypass. Unlike the other variants, it does not use historical data to mistrain branches which has made it somewhat easier to mitigate if protected against V2. Instead, this discards mispredicted data which is then accessed by an attacker.

While this article focuses on on Intel hardware, all processor companies are affected from AMD to ARM. Additionally, it is not just conventional processors that are affected. Other embedded hardware such as graphics cards and IoT chips are also affected. Examples of which include the ARM 11 processors that are found in Raspberry Pis as well as other commercially available processors used in IoT devices. Meltdown affects all known Intel devices but it is easier to mitigate than Spectre which broadly affects virtually every known hardware. As time goes on, more of these hardware vulnerabilities are revealed, so ensuring your system is updated with each security patch provided by both the operating system and the firmware manufacturer is your best line of defence.

Given the severity of these risks, it is tempting to think that purchasing new hardware is necessary. However, to date no recorded attacks exploiting these vulnerabilities have been found as they are still reliant on misspeculation which, while it does occur, occurs at a relatively low rate and requires significant foresight on the part of the attacker. WoTT can help you manage these risks through our dedicated CVE scan to ensure that you are always on top of the vulnerabilities in your system.

And while you're here...

Did you know that WoTT gives you free security audits, including CVE scanning, for your first node? Sign up today.